Telomeres are one of the keys to aging. We’ve known this for decades, and the scientists who first figured it out won the Nobel Prize in 2009. (One of them was my former colleague at Johns Hopkins University, Carol Greider.) Not surprisingly, many people have been trying, ever since, to use this discovery to slow down or reverse the aging process.

No luck so far, but that doesn’t mean you can’t spend money on your telomeres.

Over the past decade or so, a number of companies have started offering to measure your telomere length, which they suggest will tell your true, biological age. Sometimes, along with these measurements, they will offer to sell you something that they claim maintains or even lengthens your telomeres, thereby making you younger. What’s all the fuss?

Well, let’s start by explaining what telomeres are. Every cell in your body contains your DNA, arranged into 23 pairs of chromosomes. (That’s the origin of the company name for 23andMe, by the way.) Your chromosomes are very long strings of DNA letters (usually written A, C, G, and T). Through a quirk of biology, the very tips of our chromosomes are special: they contain thousands of copies, repeated end-to-end, of the 6-letter sequence TTAGGG. These are the telomeres, and they are a common feature in all animals, plants, and pretty much every living thing except for some single-celled microbes.

What’s fascinating about telomeres is that they provide a molecular “clock” that you can use to tell how old a cell is–sort of. You see, each time your cells divide, they have to copy all of that DNA, and sometimes they don’t quite copy the entire telomere. Over time, your telomeres get shorter.

This means that, in theory at least, your telomere length can tell you something about your age.

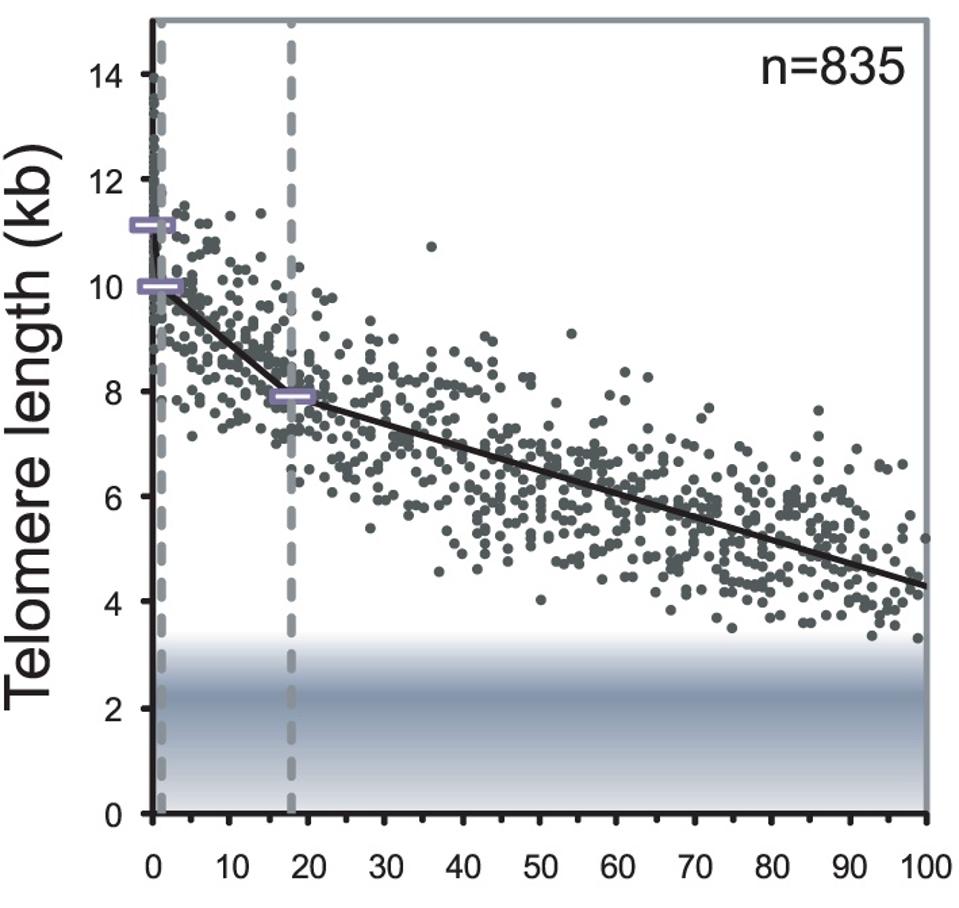

When humans are still infants, our telomeres are about 10,000 DNA letters long, and they slowly get shorter. By the time we’re in our 80s and 90s, our telomeres might be only 4000-5000 letters long–but this varies enormously. Telomere length varies from tissue to tissue–even your blood has many different types of cells in it, with different telomere lengths–and from person to person. Thus it’s entirely possible for a healthy 40-year-old to have telomere lengths that are typical of 80-year-olds, and vice versa. Here’s a graph from a scientific study that looked at telomeres in over 800 people, showing how they get shorter as you age. Length is on the vertical axis, measured in thousands, versus age on the horizontal axis:

Part of Figure 1 from “Collapse of telomere homeostasis in hematopoietic cells caused by heterozygous mutations in telomerase genes, G Aubert, GM Baerlocher, I Vulto, SS Poon, & Lansdorp, PLoS Genetics, 2012. © 2012 Aubert et al. This is an open-acce

AUBERT G, BAERLOCHER GM, VULTO I, POON SS, LANSDORP PM (2012) COLLAPSE OF TELOMERE HOMEOSTASIS IN HEMATOPOIETIC CELLS CAUSED BY HETEROZYGOUS MUTATIONS IN TELOMERASE GENES. PLOS GENET 8(5): E1002696.As you can see, telomeres decline from about 10,000 letters (bases) at birth to about 5,000 in 80-year-olds, but many people have telomeres that are thousands of bases shorter or longer than the average.

When its telomeres get too short, a cell will die. So the reasoning goes, if we can keep our telomeres nice and long, we’ll live longer! It might seem simple, but it’s not.

First, it’s not clear that there’s anything we can do if we know the length of our telomeres. As my Hopkins colleagues Mary Armanios explained, “Within the normal telomere length range, it is not possible to determine a person’s exact biologic age, nor is it a good marker of a person’s ‘youthfulness.’”

The other problem is that it’s not clear that we can take any action to make our telomeres longer, or even to prevent them from getting shorter. But there are a couple of things you can try:

Exercise regularly. There is some evidence that regular exercise is correlated with longer telomeres. A study in 2017 concluded that “adults who participate in high levels of physical activity tend to have longer telomeres, accounting for years of reduced cellular aging compared to their more sedentary counterparts.”

Avoid stress. Another study in 2016 found that stress tended to make telomeres shorter.

Even if both of those studies are wrong about telomeres, the general advice to exercise and avoid stress is good for all sorts of reasons, so I’m happy to endorse these recommendations.

In addition, there are companies (like this one) that claim you can take supplements that will maintain telomere length, but I couldn’t find any solid evidence to back up those claims. So no, you can’t take a supplement or a pill that will restore your telomeres to the lengths they had when you were a baby.

Finally, there is some promising early research that uses mRNA technology–the same technology used to develop the new COVID vaccines–to deliver enzymes that rapidly increase telomere length in human cells. A huge caveat is that this only works in cells growing in a laboratory culture, and no one knows if it’s possible to do this in a living human. But it isn’t a crazy idea, so I’ll keep an eye on this research.

So what about companies that offer to measure your telomere length? Well, they really can do it, although the accuracy of various technologies will vary. Given what we know today, it seems unlikely that these tests will provide anything of value, unless you’re among a very small cohort of people who have a telomere-related genetic disorder. So my advice is, don’t waste your money. But it can’t hurt to exercise regularly and avoid stress, and both of these pieces of advice might help maintain your telomeres as well.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Markup Key:

- <b>bold</b> = bold

- <i>italic</i> = italic

- <a href="http://www.fieldofscience.com/">FoS</a> = FoS

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.